A Pop-Culture History of Hentai

In 1814, the ukiyo-e master Katsushika Hokusai published an erotic woodblock print of a woman entwined in the arms of two octopuses. Fast forward to 2023, and “hentai”, the catchall term for X-rated anime and manga ranked as the most-searched term on the world’s largest porn website. How did Japanese erotic art evolve from clandestine woodblock prints to a globally recognized (and meme-able) corner of pop culture? The story of hentai is a tale of taboo and innovation, censorship and creativity, stretching from the Edo period pleasure quarters to the far reaches of the internet. Along the way, we’ll encounter shunga prints and censored samurai, scandalous schoolgirl comics, tentacled monsters, and the ever-shifting line between art, obscenity, and entertainment.

“Spring Pictures” in the Edo Era: Shunga’s Sensual Origins

Hentai’s roots reach back to the vibrant erotic art of Japan’s Edo period (1603–1868). In an era before photography, pleasure came in the form of shunga, literally “spring pictures,” a euphemism for erotic illustrations. These explicit woodblock prints were anything but underground. Samurai, merchants, and housewives alike indulged in shunga, sometimes even carrying them as lucky charms or bridal gifts. Sexual openness was woven into the culture; communal bathhouses and a thriving pleasure quarter meant that erotic imagery wasn’t shocking so much as everyday.

Renowned artists of the day dabbled in shunga for both artistic and financial reasons. Hokusai (best known for The Great Wave) created what is perhaps the most infamous shunga piece: The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife (1814), depicting a young woman in a decidedly amorous encounter with a pair of octopuses. Explicit, fantastical, and artfully rendered, Hokusai’s print shows that the Edo imagination had few limits when it came to erotic fantasy. And importantly, shunga set a precedent. It proved that in visual art, anything the artist could dream, no matter how bizarre or taboo, could be put to paper. It was a creative freedom that would later echo in modern hentai’s limitless kinks.

Despite its popularity, shunga eventually fell afoul of changing times. As the Meiji Restoration began in 1868 and Japan opened to the West, Victorian prudishness and new technology started to erode the shunga tradition. Photographic prints imported from Europe became the new medium for erotica, outcompeting the woodblock prints, and the Meiji government frowned on the explicit art form. By the late 19th century, open display of shunga had largely faded, marking the end of an era. But the legacy of those “spring pictures” endured, seeding an artistic lineage that would later blossom into modern hentai.

Meiji to Taishō: Sexology, Censorship, and the Birth of “Hentai”

When Japan modernized during the Meiji era (1868–1912), the nation got an infusion of Western science including the novel field of sexology. It was in this context that the term “hentai” first slithered into the Japanese vocabulary. In ordinary Japanese, hentai simply means “transformation” or “metamorphosis.” But Meiji scholars gave it a new twist: they used hentai to denote abnormality or perversity in a psychological sense. By the 1890s and early 1900s, Japanese doctors and translators were avidly reading European texts on sexual deviance, and in 1913, Austro-German sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s infamous catalog of paraphilias, Psychopathia Sexualis, was translated into Japanese under the title Hentai Seiyoku Shinrigaku, “The Psychology of Perverse Sexual Desire”. In other words, hentai had officially entered the lexicon as a clinical term for “abnormal” sexuality.

Crucially, hentai in this period did not yet mean cartoon porn. It was an academic buzzword roughly akin to “perversion.” But it didn’t stay in the ivory tower for long. By the 1910s, popular journals were splashing the word hentai across their covers to entice readers with tales of deviance and desire. In 1917 a magazine called Hentai Shinri (“Abnormal Psychology”) launched, bringing scholarly discussions of hypnosis, fetishes and madness to the public. Soon, hentai became paired with seiyoku (sexual desire) in everyday discourse, and the combined phrase hentai seiyoku (perverse sexual desire) became a catch-all for everything from voyeurism to gay love to “unnatural” lusts.

This era also saw Japan’s first modern obscenity laws. The Meiji Criminal Code of 1907 introduced Article 175, a statute banning the sale or distribution of “obscene” materials. Exactly what counted as “obscene” was left vague, but authorities generally took it to mean any explicit depiction of genitalia or sex acts. (In fact, even mere pubic hair was considered too indecent to show for a time.) The stage was set for a game of cat-and-mouse between censors and artists; one that hentai creators would be playing for the next century.

As Japan entered the Taishō period (1912–1926), the country experienced a flourishing of liberal ideas and artistic experimentation often compared to the Roaring Twenties in the West. Sexual discourse, now turbo-charged with that word hentai, was surprisingly prominent. At least ten new magazines devoted to “abnormal” sex launched in the 1920s with titles like Hentai Shiryō (“Perverse Materials”) and Gurotesuku (“Grotesque”). These publications, along with advice columns by self-anointed “sex experts,” dished on everything from fetishes and prostitution to homosexuality and sadomasochism. What had been hush-hush in polite society was now devoured as salacious entertainment under the gloss of pop science. Japan was in the midst of what one writer called a “hentai boom”. A heightened fascination with the outré sides of sexuality, even as the country strove for modern respectability.

Ero Guro Nansensu: Decadent Thrills in the 1920s

All this talk of hentai seiyoku helped spark a broader cultural movement in the late 1920s known as ero guro nansensu, literally “erotic, grotesque, nonsense.” As the moniker suggests, it was a celebration of the deviant and the absurd. A whirlwind of art and literature that gleefully mixed sex, death, and the bizarre. More than a genre, ero guro was an attitude: the embodiment of Jazz Age Japan’s hedonistic, freewheeling underbelly. It wasn’t exactly pornography or exactly horror, but a lurid cocktail of both. Common themes included bondage, dismemberment, freakish monsters, and the kind of sexual scenarios that would make even a hardened burlesque star blush.

One of the era’s literary stars was Edogawa Rampo (a pen name paying homage to Edgar Allan Poe). Rampo wrote popular mystery-horror tales that frequently veered into the sexually macabre. In stories like “The Human Chair” and “The Stalker in the Attic,” respectable facades conceal perverse obsessions, a man hides inside a chair to feel women sitting on him; a bored lodger drops poison through a ceiling hole into his neighbor’s mouth just for kicks. By the 1930s, Rampo fully embraced ero guro sensibilities: his plots featured what his contemporaries termed hentai seiyoku, or abnormal sexuality. It included sadomasochism and even a gay doctor’s obsession with a young man in The Demon of the Lonely Isle (1929). These transgressive elements helped sell Rampo’s magazines to a thrill-hungry public, even as moralists decried the “corruption” of society.

The appetite for titillation reached a ghoulish crescendo with real-life events like the Abe Sada incident of 1936, in which a former geisha erotically asphyxiated her lover and infamously severed his genitals as a keepsake. The sensational case dominated headlines and seemed to blur the line between ero guro fiction and reality. By this point, the phrase ero guro nansensu had entered common parlance to describe the national obsession with the perverse and bizarre.

Inevitably, a backlash came. With the rise of militarism in the 1930s, Japan’s government grew intolerant of “degenerate” art. Censors began to crack down on erotic grotesque media as a threat to public morals (and perhaps a distraction from the looming war effort). In 1939, Edogawa Rampo was pressured to remove a particularly disturbing story (“The Caterpillar”) from a reprint collection; despite it having run uncensored just a few years prior. Other authors saw their works banned or sanitized. By the time World War II engulfed Japan, the brief era of permissiveness was over; ero guro excess was driven back underground.

But the genie could not be put fully back into the bottle. The concept of perverse sexuality (hentai), had firmly rooted itself in the Japanese imagination. It would bide its time through the war years, waiting for another chance to re-emerge, even more vividly, in a new form.

Post-War Pulp: Occupation Censorship and the Pinks and Perils of the 1950s

In August 1945, Japan’s defeat in WWII brought about not only a political revolution, but a sexual one. During the American-led Allied Occupation (1945–1952), strict censorship was imposed on all print and film media. Under the occupiers’ rules, any sexually explicit material (which had thrived in the wild days of the ’20s) was flatly forbidden. Ironically, this Western purge was even stricter than Japan’s pre-war stance. The result was a few years of enforced chastity in publishing.

Yet as soon as the occupation ended in the early 1950s, Japan’s erotic imagination came roaring back. The immediate post-war years saw a boom in cheap, ragged-edge men’s magazines known as “kasutori” magazines. Titles like Kitan Club, Amatoria and Romance popped up on newsstands, offering a mix of lurid crime stories, pin-up photography, and frank sexual content that hadn’t been seen in years. These magazines were printed on the cheapest paper (sometimes the ink would come off on your fingers) and often folded after a handful of issues, but they were devoured by a public starved for risque entertainment. Within their pages, one could find everything from tame nudes to surprisingly hardcore fiction. Notably, Kitan Club, first published in 1947, introduced Japanese readers to S&M and bondage themes, effectively sparking the first wave of BDSM subculture in Japan.

It was in this era that Japan’s infamous obscenity law, Article 175, was tested and clarified. The law remained on the books, but publishers learned that if they avoided direct depictions of genitals (usually by covering them with convenient shadows or blurs), they could push the envelope pretty far. A legal precedent emerged: explicit sex was permissible in art as long as the offending bits were obscured. Resulting in the birth of what we know as Mosaic Censorship. This compromise would define Japanese adult media for decades. By the mid-1950s, nude photos (with any pubic hair airbrushed out) and erotic manga stories were commonplace in certain magazines, kept technically legal by strategic self-censorship.

At the same time, Japan’s film industry developed its own workaround to offer sexual content: the rise of the “pink film.” These were low-budget softcore erotic movies that began appearing in 1962 and soon flooded theaters. By the late 1960s, pink films reportedly accounted for over 70% of domestic films produced in Japan. Audiences, it turned out, had a huge appetite for erotic entertainment, even under constraints. The pink films featured ample nudity and simulated sex, but like print publishers, directors obeyed the letter of the law: no spread genitals on camera, ever. Thus, blankets, camera angles, and foggy shower-glass became the filmmakers’ best friends.

In print and on screen, Japanese artists were growing adept at dancing around the limits of obscenity. This “see-no-evil” game of censorship by omission would directly influence the strategies of later hentai manga and anime creators. But before we get to explicit cartoons, we must talk about the implicit ones: the mainstream manga of the 1960s, and a maverick artist who blew the doors off what was acceptable in comics.

Manga Mutations: Tezuka, Nagai and the Erotic Turn in Comics

While adult magazines and films were pushing sexual boundaries, Japanese manga (comics) were, for a time, left to the kids. In the 1950s and early ’60s, comics were generally seen as children’s entertainment. Osamu Tezuka’s whimsical tales like Astro Boy set the tone, and most manga magazines kept things squeaky clean. That began to change in the late 1960s, as the first generation of post-war youth became teenagers and young adults hungry for edgier fare. A wave of gritty, mature-themed manga known as gekiga (“dramatic pictures”) emerged, driven by artists like Yoshihiro Tatsumi. In these stories, published in rental booklets and niche magazines, one could find crime, violence, and yes, sex. The groundwork for adult comics was laid.

Even Tezuka, the so-called “God of Manga”, eventually rode this wave. In 1969, Tezuka’s own studio Mushi Production released “Animerama,” a series of experimental animated feature films aimed squarely at adults. The first of them, One Thousand and One Nights (Senya Ichiya Monogatari), was a psychedelic erotic epic loosely inspired by Arabian Nights. At 130 minutes, it holds the distinction of being the world’s first erotic animated feature film, and one of the longest animated films ever made. Its follow-up, Cleopatra (1970), about the famed Egyptian queen, was advertised with the titillating tagline “as far more erotic than 1001 Nights.” These films, with their mix of artistic experimentation and softcore sensuality, were essentially animated counterparts to the pink films of the era. They were not pornography by modern standards, their sexual imagery was more symbolic and teasing than explicit, but they proved that animation could tackle adult subject matter. Tezuka had kicked open a door: cartoons weren’t just for kids.

Meanwhile in the realm of print manga, a brash young artist named Go Nagai was about to detonate a cultural bomb. In 1968, the upstart publisher Shueisha launched Weekly Shōnen Jump, a magazine that would become a juggernaut of teen manga. They tapped Nagai to create one of their debut series. Nagai’s creation, Harenchi Gakuen (“Shameless School”), started as a raucous comedy set in a middle school but it quickly earned notoriety (and millions of readers) for its shameless parade of erotic gags. This was a comic where lecherous male teachers constantly schemed to catch glimpses of the schoolgirls’ panties or nude bodies, and where the female students turned the tables with their own exhibitionistic pranks. Page after page, Harenchi Gakuen gleefully violated the previously strict taboos of shōnen (young boys’) manga.

The response was explosive. Kids loved it, Shōnen Jump’s circulation skyrocketed into the millions, and a string of live-action film adaptations followed. But parent-teacher associations and moral guardians were aghast. No manga before had so openly sexualized schoolchildren or so crudely lampooned adult authority. PTA groups staged public burnings of Shameless School comics and pressured the publisher to cancel the series. Nagai cheekily responded by making his final chapter a hyper-violent apocalypse where the cast is massacred, as if saying, “Look what you made me do.”

Despite (or because of) the controversy, Nagai’s impact was undeniable. Until Harenchi Gakuen, Japanese manga had been relatively tame affairs, but things soon changed. Nagai was the first to introduce open eroticism into modern manga, effectively becoming the creator of modern erotic manga. He proved that sexual content could exist in comics and sell phenomenally well. The door Tezuka cracked open, Nagai kicked down with irreverent glee. By the early 1970s, the era of “pure” boys’ and girls’ manga was ove. A new era of boundary-pushing content had begun.

Throughout the 1970s, adult-oriented manga magazines multiplied, allowing creators to explore more explicit sexual themes away from children’s eyes. Japan’s comics industry neatly split into demographic tiers: wholesome fare for kids and teens, and separate seinen (young men’s) or rediisu (ladies’) magazines for mature content. Erotic manga of various stripes flourished in the seinen realm, from grim crime tales with rape-revenge subplots to more straightforward pin-up serials. By the end of the ’70s, a robust infrastructure was in place for producing and distributing erotic comics with publishers mindful to self-censor just enough to avoid the wrath of Article 175. The stage was now set for hentai as we think of it today to make its grand entrance. All it needed was the right combination of subculture trends and technological innovation. Enter the 1980s: the decade where it all came together.

The Lolicon Boom: Otaku Culture and the Dawn of Modern Hentai

In the early 1980s, Japan experienced another surge of sexual frankness in media, but this time, it unfolded in the realm of otaku culture (geek fandom). The convergence of comics, anime, and sexual themes gave birth to the modern idea of “hentai” as animated/manga porn. Central to this evolution was the emergence of lolicon and bishōjo genres.

The term “lolicon”, a Japanese contraction of “Lolita complex,” refers to attraction to very young-looking girls (a term inspired, of course, by Nabokov’s Lolita). In practice, lolicon in otaku media came to mean art and stories featuring childlike or prepubescent female characters in sexual or erotic situations. This sounds disturbing (and it was controversial) but in the context of 1980s manga, it often meant hyper-stylized, doe-eyed cartoon girls in frilly dresses engaging in cheeky (if sometimes explicit) adventures. A crucial point is that these were fictional characters drawn in a cute, almost innocent style, dubbed “bishōjo” (beautiful young girl) style. The bishōjo aesthetic, with its big-eyed, round-faced anime girls, took off in the late ’70s and early ’80s and quickly found its way into adult comics. In fact, bishōjo as a term is reserved almost exclusively for fictional characters, emphasizing that these were idealized “girl-next-door” fantasies rather than real minors.

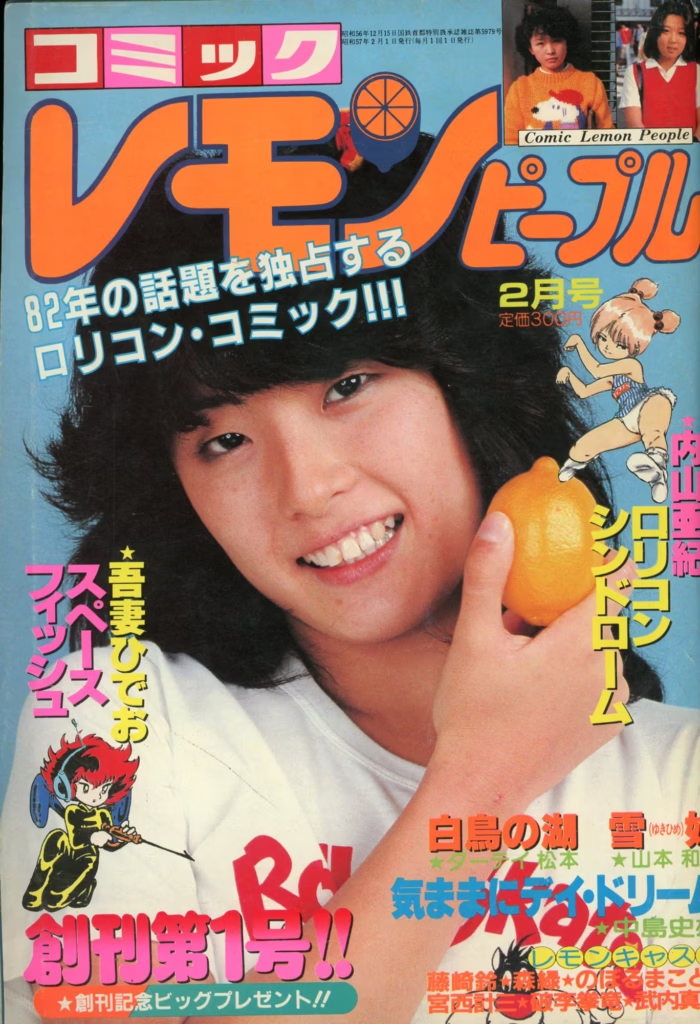

Around 1981–1982, a “lolicon boom” hit. The niche magazine Lemon People (launched 1982) became a flagship of the lolicon trend, publishing erotic manga stories and pin-ups of cartoon girls in a variety of naughty scenarios. Another magazine, Manga Burikko, pivoted to lolicon content around the same time and even featured female artists contributing work. A reminder that the creation and consumption of these fantasies weren’t exclusively male. Professional and amateur artists alike poured into this new genre; it was as if a generation of manga creators raised on cute anime (like Candy Candy and Heidi on TV) suddenly decided to remix those wholesome characters into cheeky adult parodies.

By the mid-’80s, specialty lolicon publications and dōjinshi (fan-made comics sold at conventions) were ubiquitous. The content ranged from relatively mild erotica (sexy pin-up drawings of popular anime girls) to outright hardcore depictions. One famous example of how mainstream and lolicon culture intersected is the anime “Magical Princess Minky Momo” (1982): ostensibly a kids’ show about a little girl who can transform into an adult woman to do good deeds. The premise itself flirted with lolicon themes, and adult dōjinshi of Minky Momo soon proliferated. The lines between “cute” and “sexy” were blurring in new ways.

While manga was exploring these new frontiers, anime was not far behind. Two technological trends enabled the birth of hentai anime: the spread of the VHS home video market and the rise of OVAs (Original Video Animation). Unlike television or cinema, direct-to-video anime didn’t require passing censorship boards or TV content restrictions. Creators could produce whatever they thought would sell to fans, and as it turned out, pornographic anime sold extremely well. In 1984, the first known hentai OVAs were released: one was titled Lolita Anime (no ambiguity there!), and another series named Cream Lemon soon followed. These were fully animated short films featuring explicit sex scenes, marketed via adult video stores to a largely male otaku audience. They set the template for decades of hentai anime to come: short, often fantastical scenarios (sci-fi, fantasy, or schoolyard settings) providing a framework for erotic set-pieces, typically animated in the same style as mainstream anime of the time. The content ranged from romantic vanilla encounters to far more extreme fare.

One artist in particular took advantage of the freedom of OVA animation and the loopholes of censorship to create something that would become hentai legend. Toshio Maeda, a manga artist, debuted an adult comic series in 1986 called “Urotsukidōji: Legend of the Overfiend.” It was a lurid saga of demons invading the human world, replete with ultra-violent and sexual content, and it became even more famous when adapted into an anime OVA series (1987–1989). What made Urotsukidōji notorious, and earned Maeda the nickname “The Tentacle Master”, was its creative solution to Japan’s ban on depicting penises. Maeda simply gave his rampaging demons tentacles, and had those penetrate the (often unwilling) women on screen. As Maeda later explained, “it was just a trick to get around censorship. In Japan, you’re not allowed to show a man on top of a woman… so I made it a monster.” A six-foot-long tentacle, after all, is not a human penis, it’s “just part of a monster’s body”, and thus could slip through the censors. The tentacle also freed up Maeda’s imagination: “using tentacles, I could draw women in any type of position… there was no gravity… It was creative,” he said.

Maeda’s wild invention was a hit. Urotsukidōji’s grotesque blend of sex and horror became a best-seller on home video in Japan and, eventually, a cult sensation abroad. The concept of “tentacle porn,” often thought to epitomize hentai, really exploded in the global consciousness thanks to these 1980s productions, even though Hokusai had beat Maeda to the punch by 170 years. From here on, hentai anime diversified rapidly: by the late ’80s and early ’90s, there were hentai OVAs featuring everything from mecha (giant robots) to fantasy knights to spoof parodies of popular mainstream shows. If you had an interest, there was probably a hentai version of it.

Concurrently, the otaku community was grappling with the social implications of its erotic tastes. In 1989, a criminal case shocked Japan: a young man named Tsutomu Miyazaki was arrested for the abduction and murder of four little girls. When police searched his room, they found thousands of videos, including a trove of anime and slasher films, some of which were pornographic. The media swiftly labeled him “The Otaku Murderer,” and a moral panic ensued. Suddenly, the stereotype of the harmless, anime-obsessed nerd morphed into something more sinister in the public eye. Otaku culture’s indulgence in lolicon imagery was blamed (unfairly, many argued) for desensitizing Miyazaki and his ilk. In the wake of the case, the term otaku itself took on negative connotations of social maladjustment and perversion.

Under pressure, Tokyo authorities in the early 1990s began urging publishers to tone down extreme content. Some of the most explicit lolicon manga magazines either folded or softened their approach. Prominent creators of erotic manga formed ethical self-regulation committees. Notably, however, there was no outright ban on drawn depictions of underage characters, a controversial distinction that remains to this day. (Japan finally criminalized real child pornography in 2014, but still allows fictional depictions under freedom of expression, a point of contention in international discourse.)

By the end of the 1980s, the pieces that define “hentai” were firmly in place. The word hentai itself was now commonly used by fans (especially overseas) to mean erotic anime/manga, even though in Japanese the term retained its nuance of “perversion” rather than a specific genre. Indeed, “the use of the term hentai to refer to erotic cartoons is not a Japanese but an English innovation,” scholar Mark McLelland notes; in Japan they more often say “ero anime” or just label it 18-kin (18+ only). But language aside, hentai as a distinct pop-cultural phenomenon had arrived: an umbrella covering countless fetishes and formats, unified by an attitude that anything goes as long as it’s drawn.

Globalization, Controversy & the Online Age of Hentai

In the 1990s and 2000s, hentai burst out of Japan and onto the global stage, riding the wave of international anime fandom and the advent of the internet. What was once obtainable only via specialty import VHS or seedy back-alley shops became a few clicks away for curious teenagers (and adults) around the world. With this newfound visibility came both an explosion of popularity and intense debate over censorship and cultural values.

Early anime fans in the West encountered hentai through cult labels like Anime 18, which in the 1990s distributed titles such as Urotsukidōji and La Blue Girl (a ninja-sexploitation romp) on VHS with cheeky taglines warning “Absolutely not for children.” To many outside Japan, these tapes were a mindboggling introduction to the extremes of Japanese pop culture. Tentacle demons, schoolgirl trysts, and fantastical fetishes became a late-night talking point and a not-so-secret guilty pleasure within anime club circles. By the late ’90s, “hentai” was a fixture in the lexicon of internet forums and #anime chatrooms, often eliciting equal parts intrigue and revulsion. It didn’t hurt that mainstream news occasionally ran eye-catching stories about “Japanese cartoon porn,” cementing hentai’s notoriety.

The internet then turned that trickle of exposure into a flood. As bandwidth grew and scanning/sharing fan communities proliferated, hentai manga and clips found their way onto websites, peer-to-peer networks, and eventually streaming platforms accessible from anywhere. What had been an obscure subgenre became one of the internet’s biggest attractions. (Even today, in many countries, hentai ranks among the top porn search terms, in 2023 it was again the #1 most searched term on Pornhub globally.) For a generation, the word hentai became virtually synonymous with Japanese pop eroticism.

This global spread has not been without controversy. Different countries have different legal and cultural red lines. One recurring issue is the depiction of minors in sexual contexts, something that, as noted, hentai does indulge via lolicon themes or school setting tropes. Law enforcement crackdowns have occurred: in 2009, for example, a U.S. man named Christopher Handley was prosecuted and jailed simply for ordering manga books that included illustrated lolicon scenes. It was one of the first cases to treat drawn images as equivalent to illicit pornography; Handley’s conviction sent a chill through overseas hentai collectors and raised questions about art, obscenity, and free speech. (The Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, an organization dedicated to comics free expression, even weighed in to support his defense, arguing that criminalizing manga possession amounted to a “thought crime.”) Similarly, in Canada and Australia, customs agents have seized and banned imported hentai manga under child pornography statutes, even though the material is fictional. These cases highlight a peculiar aspect of hentai’s globalization: the content acceptable in its country of origin can be deemed criminal elsewhere.

Even within Japan, hentai continues to test boundaries. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government passed a controversial ordinance in 2010 strengthening restrictions on “nonexistent youth” in media, essentially trying to curb extreme sexual depictions of minors in manga and anime. The law was met with pushback from industry and creators (who trotted out the usual arguments about slippery slopes and suppression of art), and in practice it had limited effect beyond some titles being labeled as 18+ only. Meanwhile, Japan’s national obscenity law (that old Article 175) persists to this day, which is why hentai manga and anime produced in Japan still feature mosaic censorship over genitalia. Ironically, uncensored versions of some hentai works do exist, but they are often sold outside Japan or circulate on the internet, beyond the reach of domestic law. It’s a cat-and-mouse game where the mouse has grown wings thanks to digital distribution.

Censorship debates aside, the business of hentai is now a global industry. What was once sold furtively in a corner of a Tokyo bookstore is now available on streaming sites, specialized online shops, and even major platforms (some popular e-book services openly carry 18+ manga internationally). The range of content is staggering: subgenres and fetishes that might be too niche or impossible in live-action pornography thrive in hentai form. Do you fancy amorous giantesses? Sentient slime monsters enveloping heroes? Consensual romance between orcs and elf maidens? Animated pornography has you covered. Hentai has become, in effect, a grand catalog of human (and inhuman) sexual imagination, with tags and categories for every fantasy. Some of it is playful and sex-positive; some of it is deeply problematic or outright disturbing. Yet it all coexists under the hentai umbrella, finding its audience and market.

It’s also worth noting that women form a significant part of the hentai and erotic-dōjinshi world, not just as consumers of yaoi (male–male romance) but as creators who explore female-gaze erotica, from steamy boys’ love comics to hardcore queer fantasies. This complicates the old assumption that hentai is purely a male domain. In fact, women artists were contributing to erotic manga as far back as the ’80s lolicon boom, and today women-centric hentai content (like otome games, which are romantic/erotic visual novels for women) is a growing segment. Hentai, broadly defined, has splintered into offerings for all genders and orientations. There are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and trans hentai storylines; there are wholesome erotic romances and extreme non-consensual shockers; there are even philosophical art-porn manga that win literary awards. As the medium of manga and anime has proven capable of any genre, so too has hentai proven capable of reflecting any sexual narrative, from the mundane to the mind-bending.

After this long, strange journey, what does hentai mean in the grand scheme of pop culture? In Japan, hentai (in the sense of erotic manga/anime) still occupies a somewhat fringe, stigmatized space. It’s not something openly discussed in polite company, yet it’s undeniably a fixture of the modern media landscape. Internationally, the idea of “hentai” has been absorbed into the zeitgeist as a kind of shorthand for the eccentricities of Japanese culture. It’s joked about on late-night comedy shows; it’s referenced in internet memes and music videos; it even shows up, slyly alluded to, in mainstream video games and comics.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing is how normalized animated erotic content has become among younger audiences. Surveys have found that many teens and young adults, even outside of Japan, have been exposed to hentai imagery (whether through curiosity or by stumbling on it online). The stigma is arguably lessening, with hentai seen as just another flavor of adult entertainment. That said, its more extreme niches will likely always provoke discomfort and criticism, which in turn will fuel creators to keep testing those limits, in the grand tradition of ero-guro and shunga before them.

In the end, the history of hentai is a story of cultural adaptation and artistic freedom finding a way. What began as hand-painted scrolls and woodblock prints in the bedrooms of Edo-period nobles evolved into inked manga panels traded by students, which evolved into pixels on a screen shared by millions across the globe. Each era’s technology, the printing press, the camera, the VCR, the internet, unleashed new possibilities for erotic art, and Japanese creators enthusiastically rode each wave. Censors raised their scissors; artists raised them a tentacle. And the dance continues.

From the genteel eroticism of shunga to the garish carnival of today’s hentai, a common thread persists: an embrace of sexuality’s imaginative side. Hentai asks, “What if…?” and answers it with drawn dreams (or nightmares) unchained by physical reality. In doing so, it has carved out a unique and lasting niche in pop culture. Love it, hate it, or laugh at it, hentai is here to stay, a testament to the fact that human sexuality will always find a medium for its many forms of expression. As the Japanese might say, hentai is a bit hentai. A bit weird, a bit perverse, and that’s exactly why it’s so fascinating.

Post a comment